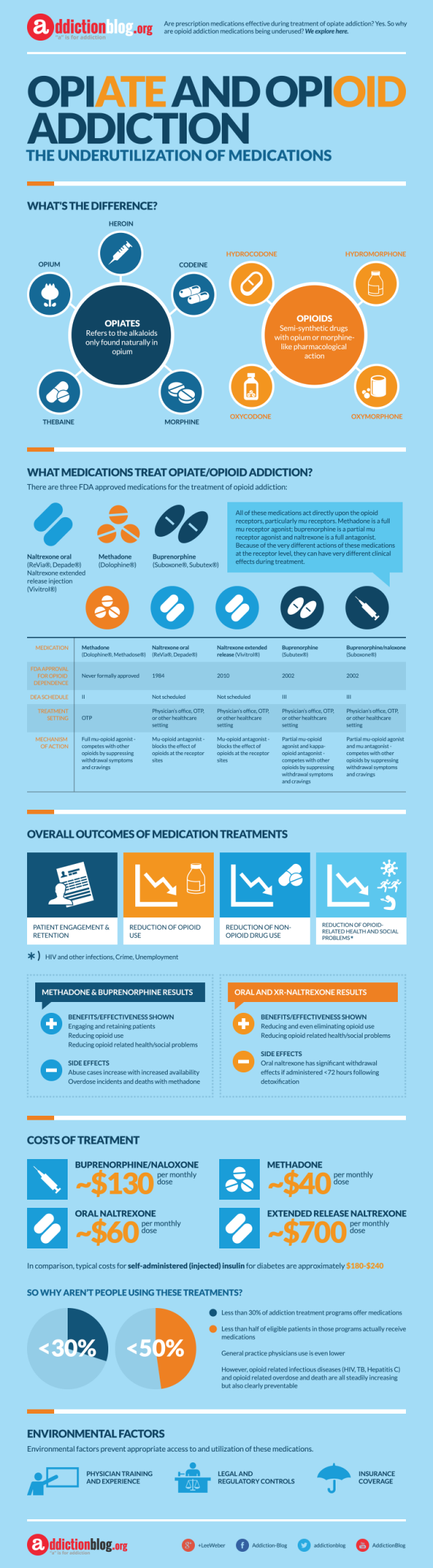

ARTICLE OVERVIEW: The “opiate” class of medications includes illegal drugs like heroin, synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, and prescription pain relievers such as oxycodone (OxyContin), hydrocodone (Vicodin), codeine, morphine, and many others. Opioid addiction is a major problem in the United States. The good news is that effective treatments exist and include behavioral therapy combine with medicines. More on successful treatment outcomes below.

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

- Definitions

- Brian Changes

- Main Uses

- Why Withdrawal Happens

- Symptoms Of Withdrawal

- Protracted Withdrawal

- Medicines For Withdrawal

- Medicines For Maintenance Therapy

- Other Treatments

- Your Questions

What Is The Difference Between Opiate And Opioids?

The answer depends on who you’re taking to. Some people carefully distinguish between these two groups of narcotic drugs when they speak about them. Other people use the two terms interchangeably or prefer one over the other.

Both opiates and opioids are used medically; they may be prescribed for pain relief, anesthesia, cough suppression, diarrhea suppression, and for treatment of opiate/opioid use disorder. In addition, people with a substance use disorder (addiction) may also use both of these types of drugs in ways that harms themselves.

So, the main difference between these type types of drugs is in how they are made.

Opiates are chemical compounds that are extracted or refined from natural plant matter (poppy sap and fibers). Examples of opiates:

- Codeine.

- Heroin.

- Morphine.

- Opium.

Opioids are chemical compounds that generally are not derived from natural plant matter. Most opioids are “made in the lab” or “synthesized.” Examples of opioids:

- Fentanyl

- Hydrocodone (e.g., Vicodin).

- Hydromorphone (e.g., Dilaudid).

- Oxycodone (e.g., Oxycontin, Percocet).

Still, both groups of drugs are “narcotics”. The term “narcotic” comes from the Greek word “stupor”, originally referring to a variety of substances that dulled the senses and relieved pain.

Brain Changes

So, how do these drug act in the brain?

They act by attaching to specific proteins called opioid receptors, which are found on nerve cells in the brain, spinal cord, gastrointestinal tract, and other organs in the body. When opiate or opioid drugs attach to their receptors, they reduce the perception of pain and can produce a sense of well-being; however, they can also produce drowsiness, mental confusion, nausea, and constipation.

Specific subtypes of opioid receptors (mu, delta, and kappa) that are activated by the body’s own (endogenous) opioid chemicals (endorphins, encephalins) typically mediate the effects of opiate and opioids. With repeated administration of these drugs, the production of endogenous opioids is inhibited, which accounts in part for the discomfort that ensues when the drugs are discontinued (withdrawal).

Opioid medications can produce a sense of well-being and pleasure because these drugs affect brain regions involved in reward. People who abuse opioids may seek to intensify their experience by taking the drug in ways other than those prescribed. See this NIAAA image of brain neurocircuits that are central to addiction [1]:

Main Uses

The pharmaceutical industry has created more than 500 different opioid molecules. Some, are widely used medically, some are not. Examples of well-known opioids used medically in the United States are:

- Dextromethorphan (NyQuil, Robitussin, TheraFlu, Vicks).

- Dextropropoxyphene (Darvocet-N, Darvon).

- Hydrocodone (Vicodin).

- Oxycodone Oxycontin, Percocet)

- Oxymorphone (Opana).

- Meperidine (Demerol).

- Methadone (Dolophine).

- Fentanyl (Ultiva, Sublimaze, Duragesic patch).

Some of the clinical uses of opioids include:

- Anesthesia involves three main aspects, which are pain relief or analgesia, loss of memory of the surgery and muscle relaxation to facilitate surgery and manipulation.

- Cough suppression, especially in the case of a dry and non-productive cough. Common cough suppressants include codeine, dihydrocodeine, ethylmorphine, hydrocodone, and hydromorphone. However, since these opioids can have other side effects, an opioid derivative called dextromethorphan is often used as a cough suppressant. Notably, dextromethorphan does not have the adverse effect of potentially becoming addictive.

- Diarrhea suppression is another side effect of opioid use is constipation and some opioids may therefore be used to control diarrhea. However, opioids are not usually used to control infective diarrheas due to the risk of serious, life threatening consequences. Drugs such as diphenoxylate and loperamide are useful in treating irritable bowel syndrome and some other organic causes of diarrhea.

- Pain relief:

a. Acute pain after surgery.

b. Cancer pain.

c. Pain arising from disease (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis). - Severe anxiety may be treated with opioids such as dihydrocodeine and oxymorphone.

- Replacement therapy via specific opioids such as methadone and buprenorphine are used to help wean persons off some of the more potent opioids such as heroin. Methadone is given in low doses after stopping heroin to reduce dependency on the opioid but without causing severe withdrawal symptoms.

However, even the medical use of opioids comes with risks. See this ASAM 2016 Statistics Document for more on the facts and figures triggered by the use of prescription painkillers in the U.S. [2]

Why Withdrawal Happens

Opioid withdrawal is one of the most powerful factors that drive addictive behaviors. In fact, many people with a drug problem keep using just to avoid it. However, treatment of the person’s withdrawal symptoms is based on understanding how withdrawal is related to the brain’s adjustment to opioids.

Repeated exposure to escalating dosages of opioids alters the brain so that it functions more or less normally when the drugs are present and abnormally when they are not. Two clinically important outcomes are opioid tolerance (the need to take higher and higher dosages of drugs to achieve the same opioid effect) and drug dependence. [3] [4]

Opioid tolerance occurs because the brain cells that have opioid receptors on them gradually become less responsive to the opioid stimulation. Withdrawal symptoms occur only in persons who have developed dependence.

Main Symptoms of Withdrawal

According to this 1994 medical journal article published in Addiction magazine, “Opiate withdrawal”, the process of detox from opioids and opiates has been described as akin to a moderate to severe flu-like illness. Opiate withdrawal is described as subjectively severe but objectively mild. In other words, withdrawal is rarely medically threatening but can be incredibly uncomfortable. [5]

Early symptoms of withdrawal include:

- Agitation.

- Anxiety.

- Increased tearing.

- Insomnia.

- Muscle aches.

- Runny nose.

- Sweating.

- Yawning.

Late symptoms of withdrawal include:

- Abdominal cramping.

- Diarrhea.

- Dilated pupils.

- Goose bumps.

- Nausea.

- Vomiting.

These symptoms are very uncomfortable, but are not life threatening.

NOTE HERE: When you go through withdrawal, your tolerance drops. This contributes to the high risk of overdose during a relapse. Users may initially take the high dosage that they previously had used before quitting, a dosage that produces an overdose in the person who no longer has tolerance.

Protracted Withdrawal

Accroding to this SAMHSA Treatment Advisory, some symptoms of withdrawal are “protracted”…or appear in the weeks and months after last drug use. This type of withdrawal, strictly defined, is the presence of substance-specific signs and symptoms common to acute withdrawal but persisting beyond the generally expected timeline.

Protracted withdrawal signs and symptoms for opiates or opioids can include:

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Mood disorders

- Sleep disturbances

…that can last for weeks or months following initial withdrawal. Other possible symptoms include fatigue, dysphoria (feeling down or emotionally blunted), and irritability.

Additionally, withdrawal symptoms may affect cognition and thinking. A small National Institutes of Health study found that people who had quit opioids for a prolonged period of time showed decreased ability to focus on a task compared with subjects who had never used opioids. People in recovery from heroin dependence also show deficits in executive control functions that may persist for months beyond the period of acute withdrawal. [6]

Medicines for Withdrawal

Treating withdrawal symptoms reduces the severity of experience, which increases the chances of successful detox and continuing to different treatment options. In other words, why suffer through withdrawal when you can address symptoms…and make them less intense?!

The main medicines used to treat opiate/opioid withdrawal include:

1. Clonidine is an antihypertensive drug that has been used to facilitate opioid withdrawal in both inpatients and outpatients for more than 25 years. It works by binding to α2 autoreceptors at the coeruleus locus and suppresses its hyperactivity during abstinence. Doses of 0.4 to 1.2 mg per day or more reduce many of the autonomous components of the opioid withdrawal syndrome, but symptoms such as insomnia, lethargy, muscle aches and restlessness may not be managed properly. Lofexidine is an analogue of clonidine, has been approved in the United Kingdom and can be as effective as clonidine for opioid withdrawal with less hypotension and sedation. The combination of lofexidine with low doses of naloxone appears to improve retention symptoms and time to relapse.

2. Benzodiazepines like clonazepam, trazodone and Zolpidem have been used for insomnia related to abstinence, but the decision to use a benzodiazepine should be taken with care, especially for outpatient detoxification.

3. Symptomatic treatment. This includes non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen or ketorolac tromethamine used for muscle cramps or pain; bismuth subsalicylate for diarrhea; prochlorperazine or ondansetron for nausea and vomiting; and a2-adrenergic agents (e.g., clonidine) for flu-like symptoms. Vitamin and mineral supplements are often administered.

4. Antidepressants. Anyone going though detox for opiates should be checked for depression and other mental illnesses. Treating these disorders can reduce the risk of relapse. Antidepressant medicines should be given as needed.

Medicines for Maintenance Therapy

According to the World Health Organization, the essential medicines for opiate dependence is methadone and buprenorphine. [7] In fact, the most effective pharmacological treatment for opioid dependence is maintenance therapy with opiate agonists like methadone, followed by maintenance therapy with opioid agonists with buprenorphine and naltrexone. These agents can be used both for opiate extraction and for maintenance treatment.

Treatment for opioid addiction requires long-term management. Behavioral interventions alone have extremely poor outcomes, with more than 80% of persons returning to drug use. Similarly, poor results are observed with medication-assisted detoxification. The three drugs approved by the FDA for the long-term treatment of opioid dependence are the following:

1. Buprenorphine. Its action on the mu opioid receptors elicits two different therapeutic responses within the brain cells, depending on the dose. At low doses, buprenorphine has effects like methadone, but at high doses, it behaves like naltrexone, blocking the receptors so strongly that it can precipitate withdrawal in highly dependent persons.

Buprenorphine offers a safety advantage over methadone and LAAM, since high doses precipitate withdrawal rather than the suppression of consciousness and respiration seen in overdoses of methadone, LAAM, and the addictive opioids. Buprenorphine can be given three times per week. Buprenorphine is available in 4 mg and 8 mg tablets. The maintenance dose of the combination tablet can be up to 24 mg and used for every-other-day dosing. Buprenorphine has less overdose potential than methadone, since it blocks other opioids and even itself as the dosage increases.

2. Methadone is a long-acting opioid medication that causes dependence, but, because of its steadier influence on the mu opioid receptors, it produces minimal tolerance and alleviates craving and compulsive drug use. Methadone treatment reduces relapse rates, facilitates behavioral therapy, and enables persons to concentrate on life tasks such as maintaining relationships and holding jobs.

People are generally started on a daily dose of 20 mg to 30 mg of methadone, with increases of 5 mg to 10 mg until a dose of 60 mg to 100 mg per day is achieved. The higher doses produce full suppression of opioid craving and, consequently, opioid-free urine tests. They generally stay on methadone for 6 months to 3 years, some much longer. Relapse is common among persons who discontinue methadone after only 2 years or less, and many persons have benefited from lifelong methadone maintenance.

3. Naltrexone is used to help persons avoid relapse after they have been detoxified from opioid dependence. Its main therapeutic action is to monopolize mu opioid receptors in the brain so that addictive opioids cannot link up with them and stimulate the brain’s reward system. Naltrexone clings to the mu opioid receptors 100 times more strongly than opioids do, but it does not promote the brain processes that produce feelings of pleasure. Naltrexone is given at 50 mg per day or up to 200 mg twice weekly.

Many people think that maintenance medication is substituting one addiction for another. But extensive literature and systematic reviews show that maintenance treatment with methadone or buprenorphine is associated with positive outcomes such as:

- Retention in treatment

- Reduction in the consumption of illicit opiates

- Decreased cravings

- Improved social function.

Want to read more? Check out this SAMSHA TIP on Treatments for Opioid Use Disorders. [8]

Maintenance treatment should be offered in combination with psychosocial support. Together, medicines and talk therapy can help people stay off drugs!

Other Treatments

Withdrawal from these drugs on your own can be very hard and may be dangerous. Treatment most often involves medicines, as we explain above, counseling and support. Indeed, withdrawal can take place in a number of settings, including [9]:

- At home, using medicines and a strong support system. This method is difficult, and withdrawal should be done very slowly using a doctor supervised taper.

- In a regular hospital, if symptoms are severe.

- Inpatient treatment.

- Intensive outpatient treatment often called “day hospitalization”.

Most people need long-term treatment after detox. This can include:

- Outpatient counseling.

- Self-help groups, like Narcotics Anonymous or SMART Recovery.

- Using facilities set up to help people detox.

Your Questions

Still have questions about opiate and use or how to treat a problem? Please leave your question below, and we will answer it as soon as possible. If we do not know the answer we will refer you someone who can help.

Remember, you are not alone.

Or, call us on the hotline number listed on this page.

You can get better!

Related Posts